Introduction

If you are new to BASH and Linux, don't you worry the community is the driving force here. If someone's stuck somewhere, the platforms, forums, and blogs are ready to help anyone there. BASH is a short term of Bourne-Again Shell, it is a shell interface that has much more capabilities and functions than the simple Bourne shell(sh). It has some quite remarkable features and it is even capable of calling itself a programming language in some sense.

Without wasting any time on the introduction, let's keep the article rolling. In this part, I'll try to cover the basics of the following topics:

- Structure of Bash Script.

- Variables.

- If-else Conditional Statements.

- Loops.

- For loop

- While loop

- Until loop

- Functions.

Firstly, you should have some basic understanding of Linux commands such as listing directories, creating, making editing files, and some tiny little tasks. Bash scripting is the way to do these in a programmatic way, that's why it is called scripting.

Understanding a Simple Shell script

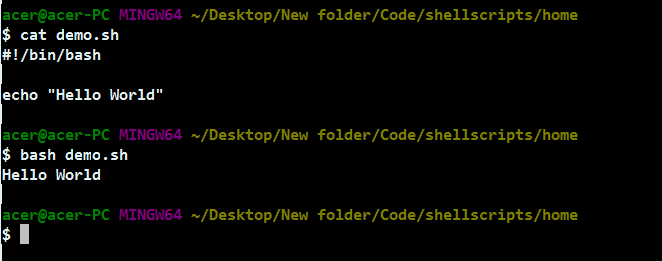

#!/bin/bash

echo "Hello World"

That is such a simple elegant script, isn't it? Well, the first command is called the she-bang which tells the Shell to execute or run the file as a Bash script or from a Bash interpreter. The next command is a simple echo which is used for printing text to the screen/console. She-bang is the path to the Bash interpreter. So, it basically redirects the shell to execute the file/script in a Bash environment.

To execute the script we have many ways, either use Bash, source, or execute it as a shell-script by making it executable from the path. In this case, I used Bash to run the script, we'll see others as well.

The core structure of the Bash script is quite simple, we can make the format of the script according to the paradigm used and objective of the script. For basic scripts which has utility functions we normally declare those in the beginning after the she-bang header. After the function, we can have the core main part of the script. It was enough and important here to understand the purpose of the she-bang header and how to execute a shell script.

Variables

Definitely, we need variables to store some value which we are gonna use again and again. Bash has variables but without any specific data types, you can store anything in anything. It becomes a mess in comparing to variables and their values :( Though it might be a feature, not a bug sometimes.

Let's create some variables in a Bash script.

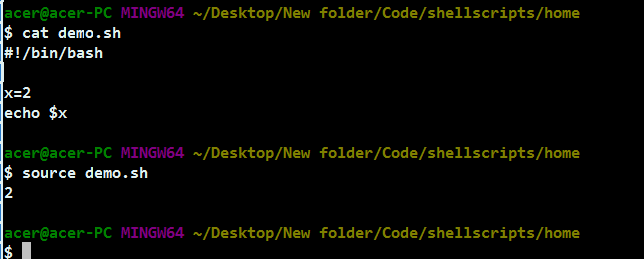

#!/bin/bash

x=2

echo $x

To create a variable, we simply write the variable name and assign it to whatever we want. DO NOT leave spaces before and after assignment operator(=), it won't work. To access the value of the variable we use the $ symbol. That is about the variables, If you want to perform some arithmetic on variables, it is covered in the further sections.

From the above script, we outputted the value of x to the console. We also executed the script file using the source command.

If-else Conditional statements

If-else conditional statements are quite the fundamentals of any logical operations performed in the programming world, so Bash has them implemented pretty much the same way as other shells do.

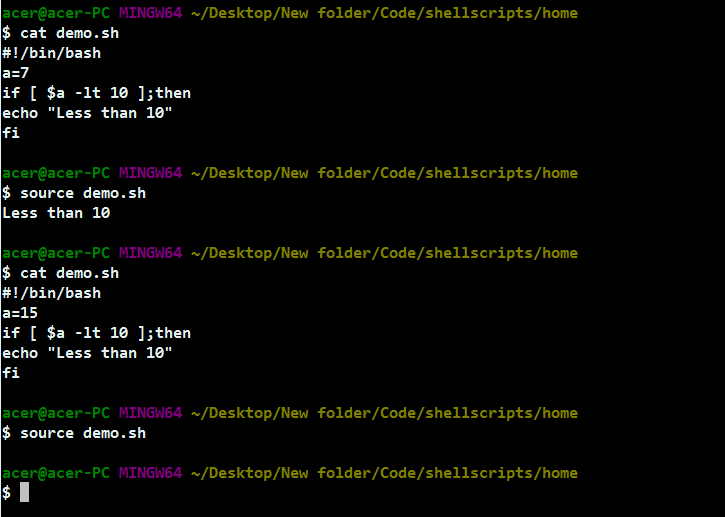

#!/bin/bash

a=9

if [ $a -lt 10 ];then

echo "Less than 10"

fi

We use "If", followed by "then" to execute the mentioned commands after that until it hits "fi" or else statement, we'll see else and if-else block after this. That is a basic If statement, here if we are comparing numbers we use -lt for less than, -gt for greater than, -eq for equals to, -ne for not equals to, -le for less than equals to, and -ge for greater than equals to. For string comparison, we use symbols such as < for less than, > for greater than, = for equals to, != for not equals to.

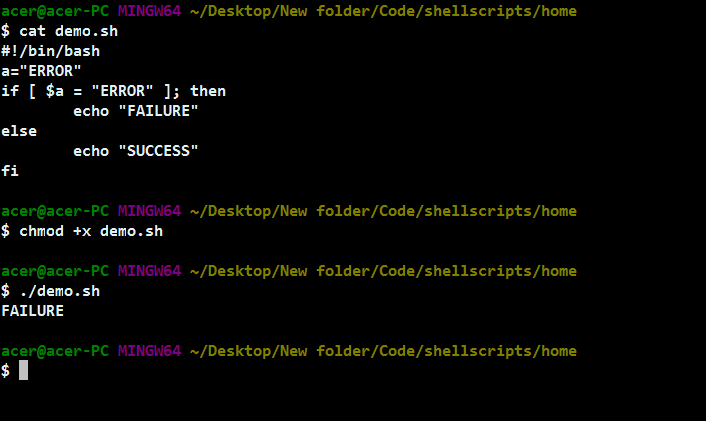

#!/bin/bash

a="ERROR"

if [ $a = "ERROR" ]; then

echo "FAILURE"

else

echo "SUCCESS"

fi

In the above example, we have used the if-else block, comparing a string with other and using the = operator to compare. It's quite interesting that Bash has string comparison built-in, unlike C/C++ where we have to depend on external libraries. We have used chmod to make the script file executable to anyone using the system. And then we simply put in the path to the file to run it.

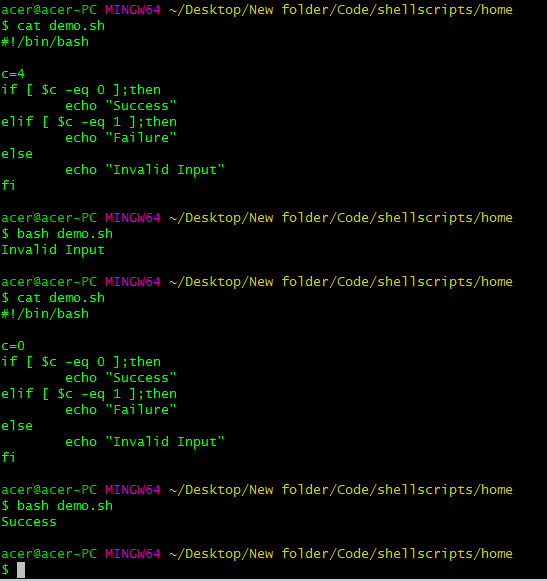

#!/bin/bash

c=3

if [ $c -eq 0 ];then

echo "Success"

elif [ $c -eq 1 ];then

echo "Failure"

else

echo "Invalid Input"

fi

From the above script, we used if-elif-else statements to evaluate different conditions. We had use -eq to equate the value of the variable to the number we want to compare with. That was self-explanatory logic.

Loops

We have 3 types of loop statements in Bash, they are:

- For loop

- While loop

- Until loop

For loops

In for loop, we have the freedom to use in range-bound or C-like for loops. Let us take a look at both of them using examples.

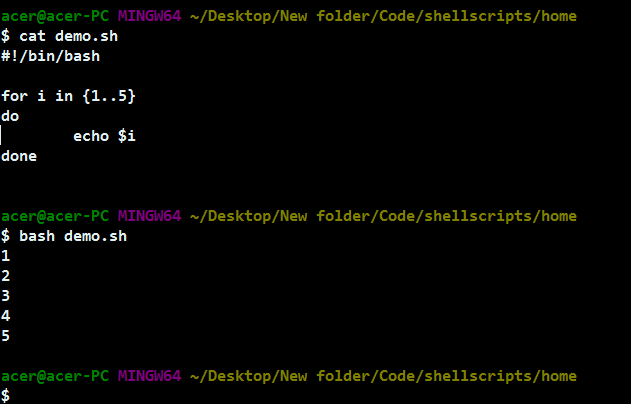

#!/bin/bash

for i in {1..5}

do

echo $i

done

The above loop was used as a range-based loop, which loops through 1 and 5 inclusive. We use {} to use it as the range. As "then" and "fi" in if conditions, we have "do" and "done" in loops. Between the do and done statements, we can type in the statements we want to loop.

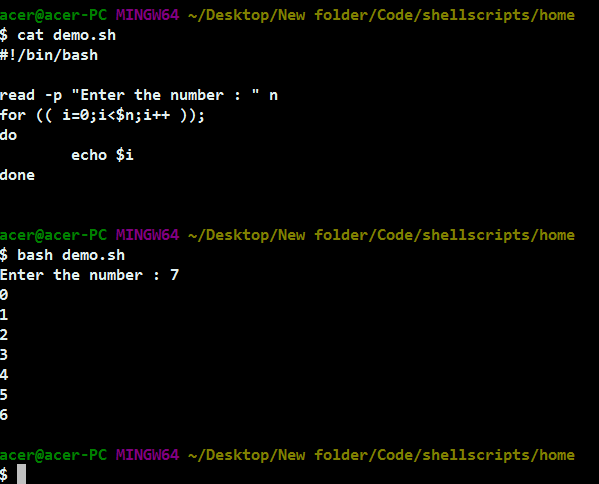

#!/bin/bash

read -p "Enter the number : " n

for (( i=0;i<$n;i++ ));

do

echo $i

done

The above for loop is a typical C-style for loop which takes 3 arguments, the initializing iterator, the condition, and the incrementor. We surround the arguments with double braces followed by a semi-colon. The rest of the syntax is identical to the previous for loop style.

While loops

While loops are used quite commonly in Bash and the syntax is quite straightforward.

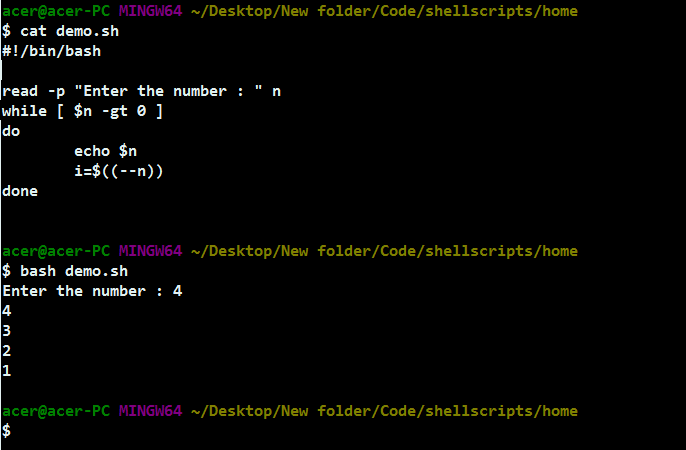

#!/bin/bash

read -p "Enter the number : " n

while [ $n -gt 0 ]

do

echo $n

i=$((--n))

done

The above while loop has a condition for the number to be greater than zero. We take in the input from the user using the command read and store it in the variable n, the -p is an argument to prompt the user with text before the input. We use the decrement operator to decrement the iterator. The syntax is quite similar and easy to understand. As usual in loops, we have do and done to start and end the loop.

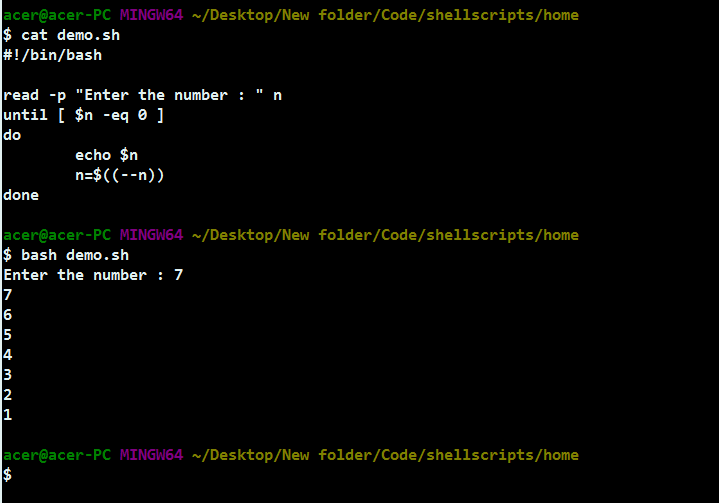

Until loops.

Until loop is a while loop but with the opposite condition, we loop until a certain criterion is not matched.

#!/bin/bash

read -p "Enter the number : " n

until [ $n -eq 0 ]

do

echo $n

n=$((--n))

done

In the loop, we iterate over and over again until n becomes 0. Until is simply to exit from the loop until a certain condition is met. The rest of the syntax is again the same as the other loop with do and done statements.

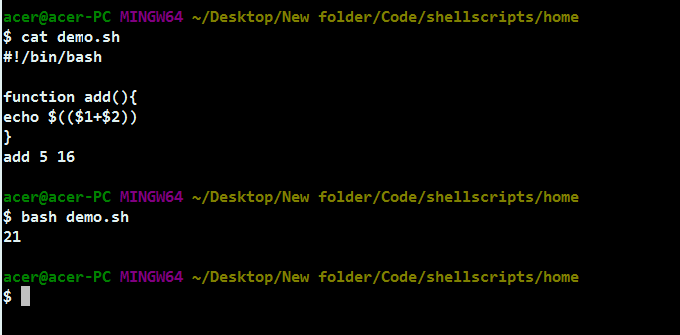

Functions

Functions are the part and parcel of any script, we don't use it necessarily, but they come in handy quite some times and serve the purpose absolutely well. We can customize what we want to return from the function depending on the needs.

#!/bin/bash

function add(){

echo $(($1+$2))

}

add 3 6

In Bash functions, we do not pass arguments inside brackets, we have to pass in parameters as space-separated values after the function name in the function call. This also means that we can pass any number of parameters to a function, but only we should handle them properly. Otherwise, there is no use in passing unlimited parameters to a function. This is really powerful but it needs to be used wisely to have its full potential. Also, it not mandatory to use the keyword "function" before the name, So you could also write just the name and the rest of it as it is.

#!/bin/bash

add(){

echo $(($1+$2))

}

add 3 6

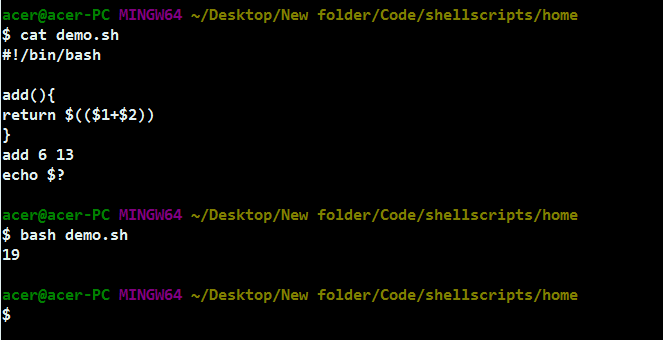

The return statement in functions is also quite an important aspect in logical programs. But it is not like returning values from a function, it is like returning the exit status of a function scope, so it can return inappropriate behavior from the shell depending on the return value.

#!/bin/bash

add(){

return $(($1+$2))

}

add 6 13

echo $?

Here we return the addition of two numbers and we use the internal variable ? To access the exit status of the function. The ? Is an internal variable in Bash, which holds the exit status of the last executed command. In this case, it was the function call and its return statement was stored in it. As said, it can become quite buggy to exit the function scope with wired return statements, so to avoid those we can make use of global variables.

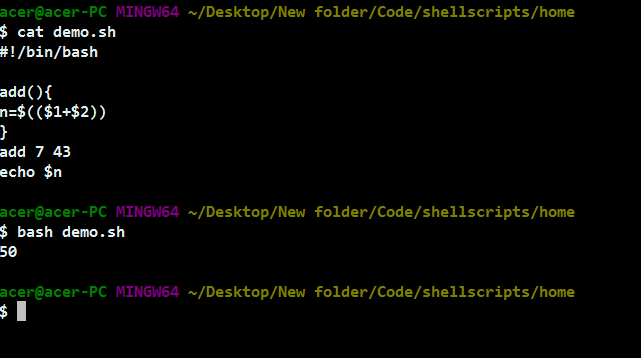

#!/bin/bash

add(){

n=$(($1+$2))

}

add 5 16

echo $n

In the above program, we use n as a global variable to access out of the function scope. Function in Bash can also return multiple values at once but that can be buggy at times, so I don't recommend that.

So, that is the basics of Bash functions covered.

This is it from the Bash scripting guide Part-1, I'll cover more topics in the upcoming parts of the series.